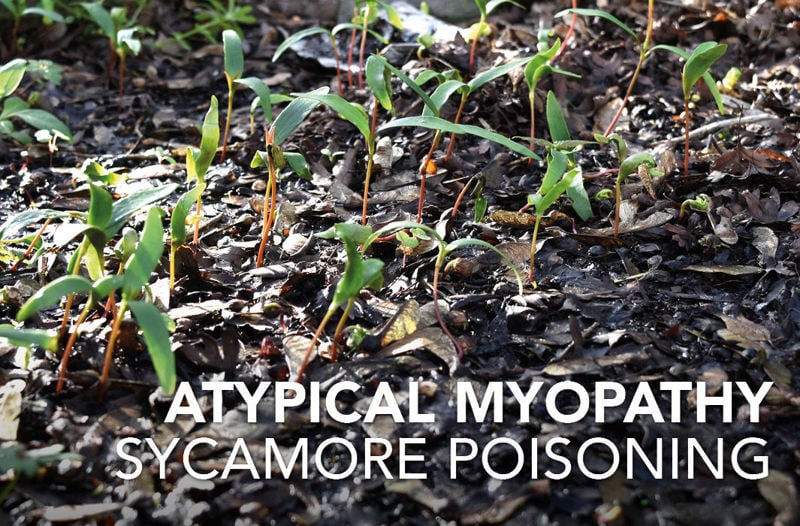

- Atypical myopathy, also known as Sycamore poisoning, is a severe and often fatal muscle disorder caused by the ingestion of sycamore ‘helicopter’ seeds, seedlings and to a lesser degree the leaves of the sycamore tree (Bates, 2022).

Research has shown that Atypical myopathy only affects grazing horses (Votion et al. 2020) and is most commonly seen during autumn but does occasionally occur during other seasons (González-Medina et al. 2017).

Sycamore seeds, seedlings and leaves contain Hypoglycin A (HGA), a toxin which, when ingested, is metabolised into compounds that slow or stop energy production in muscle cells. This particularly affects the cardiac and respiratory muscles, as well as the muscles that enable the horse to stand (Fabius and Westermann, 2018; Bates, 2022). The number of horses affected differs per year, but most horses are affected in the autumn months when sycamore seeds are present on pasture (Unger et al. 2014; Żuraw et al. 2016). This could imply that horses prefer the seeds over the seedlings (which appear in Spring), or that due to the better quality of spring grass horses do not feel the need to search for other feedstuff when out on pasture (Westermann et al. 2016).

Risk Factors

A study conducted by Votion et al. (2020) aimed to assess risk factors associated with Atypical myopathy. The authors used data from over 3000 Atypical Myopthy cases, recorded in 14 different European countries, from autumn 2006 to winter 2019. Cases were more commonly seen in Autumn (median 79.5) compared to Spring (median 24) and although horses of all ages, breeds, sex and height were affected, horses particularly at risk were those less than 3 years of age as well as those that were inactive, with a low - moderate body condition score.

Other risk factors included horses out grazing full time in a humid environment, especially where dead leaves had piled up in autumn; the presence of Sycamore trees and/or woods near grazing fields; and hay being fed from the ground during autumn months. Interestingly, out of the 14 countries data was collected from for the study the U.K. had third highest number of cases, after France and Belgium.

Symptoms

Atypical myopathy has a high mortality rate of 74% (Votion et al. 2020), with horses often succumbing to the illness within 2 – 3 days (Bates, 2022). It is worth noting that a study conducted in 2020 by Dunkel et al. found that the mortality rate of the disease dropped to 54% in horses that were quickly hospitalised. Knowing the symptoms of Atypical myopathy is therefore vital in ensuring a vet is contacted as soon as possible if the horse is suspected of having the disease.

Symptoms of Atypical myopathy include -

- Sudden onset of muscle weakness and stiffness (Bochnia et al. 2015)

- Muscle tremors (Votion & Serteyn, 2008)

- Loss of ability to stand (Brandt et al. 1997)

- Depression, often accompanied by low hanging head (Votion & Serteyn, 2008)

- Difficulty in breathing (Gonzalez-Medina et al. 2017)

- Abnormal cardiac changes (Verheyen et al. 2012)

- Dark/red coloured urine (Votion & Serteyn, 2008)

- Colic like symptoms

Although physical symptoms are mainly used for a diagnosis there are some tests your vet can conduct if Atypical myopathy is suspected. These include;

- Checking electrolyte balance (Votion, 2012)

- Checking lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase (CK) levels which indicate muscle damage (Bochnia et al. 2015)

- Checking blood and urine samples as the Hypoglycin A toxin can be found in these samples (Votion, 2012)

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for horses diagnosed with Atypical Myopathy (Votion, 2012). Current available treatment is mainly supportive and aims to increase survival rates (Fabius & Westermann, 2018). According to Fabius & Westermann (2018) treatment options include;

- Resolving dehydration and electrolyte imbalances

- Providing energy for affected muscles

- Eliminating toxins in the body

- Providing pain relief

- Prevent further intoxication and injury

Studies have also suggested that the supplementation of vitamin E, selenium, carnitine and riboflavin can support AM affected horses and can increase chances of survival (Fabius & Westermann, 2018). Vitamin E and selenium are commonly supplemented to provide general muscle support due to their antioxidant properties (Fagan et al. 2017). Because of the supportive function of vitamin E, it is believed that it is able to provide muscle support to horses diagnosed with Atypical Myopathy (Finno et al. 2006). Carnitine can increase leptin levels which stimulates glucose uptake from the bloodstream and glucose metabolism, providing vital energy for damaged muscles (Kranenburg et al. 2014). The role of Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, in the treatment of Atypical Myopathy is unknown but has also been shown to be beneficial during treatment (van Galen et al. 2012).

Prevention

Due to the high mortality rate and the absence of specific treatment, prevention is the key to avoiding Atypical Myopathy (Votion et al. 2020; Bates, 2022).

Autumn prevention

Depending on weather conditions the sycamore (helicopter) seeds have been shown to travel several hundred meters (Katul et al. 2005) so even if your field is not near any sycamore trees it is important to still be vigilant for the seeds, especially in autumn after windy weather. If your grazing is near sycamore trees and the presence of seeds is abundant it is advised to stop grazing on the affected area.

In studies conducted by both González-Medina et al. (2017) and Votion et al. (2020) horses grazing for more than six horses per day were seen to be at an increased risk of Atypical Myopathy. This suggests that the length of exposure to the toxins is a determining factor and reducing turnout during at risk times of year may help to reduce the risk of the disease, although this method should not be relied upon.

Receiving supplementary forage (hay and straw) throughout the year has been shown to decrease the risk of Atypical Myopathy (Votion et al. 2009), however feeding hay from the ground in the Autumn has been shown to be a risk factor (Votion et al. 2020). This indicates that hay fed on the ground can increase the risk of ingesting sycamore seeds material, so it is ideal to feed from haynets or raised hay feeders. If hay feeders are used ensure these are cleaned out regularly in case any seeds have found their way into the feeder.

Spring prevention

Seedlings should be removed from pasture when seen, ideally removing all roots (Votion et al. 2020). Mowing is often recommended as a method of controlling seedlings, however a study conducted by González‐Medina et al. (2019) found that there was no significant decline in Hypoglycin A (HGA), content in mowed seedlings. After one-week HGA concentration increased in grass cuttings that contained seedlings. Therefore, if using mowing as a method to remove seedlings from pasture it is vital that the mowed cuttings are removed from the pasture before horses are allowed the grass on the area.

Other prevention methods

The spreading of manure and harrowing of pastures has been shown to increase the risk of Atypical Myopathy (Votion et al. 2009). This practice is likely to increase the risk of the dispersal of the seeds throughout the pasture. It is therefore advised to avoid these practices during at risk times of year.

Hypoglycin A is a water-soluble toxin that may pass from plants to water by if seeds, seedlings or leaves end up in the water (Votion et al. 2019). This may explain why a humid environment increases the risk of Atypical Myopathy, and also why it is advised that only pastures that do not contain rivers or freestanding water should be used during the risky seasons.

Summary

Atypical myopathy is a severe and often fatal muscle disorder that affects grazing animals mainly in the Autum, but also at other times of the year. It is caused by the ingestion of sycamore ‘helicopter’ seeds, seedlings and to a lesser degree the leaves of the sycamore tree. Due to its high mortality rate it is vital that preventative measures are undertaken during at risk times of year to reduce the risk of your horse being diagnosed with Atypical myopathy.

PLEASE NOTE: You should contact your vet immediately if you suspect your horse has eaten sycamore seeds, seedlings or leaves, especially as the disease progresses rapidly and has a high mortality rate.

References

- Bates, N. (2022) ‘Atypical myopathy.’, UK-Vet Equine, 6(3), pages 96-102.

- Bochnia, M., Ziegler, J., Sander, J., Uhlig, A., Schaefer, S., Vollstedt, S., Glatter, M., Abel, S., Recknagel, S., Schusser, G. F., Wensch-Dorendorf, M., & Zeyner, A. (2015) ‘Hypoglycin a content in blood and urine discriminates horses with atypical Myopathy from clinically normal horses grazing on the same pasture.’, PLoS ONE, 10(9), pages 1-15

- Brandt, K., Hinrichs, U., Glitz, F., Landes, E., Schulze, C., Deegen, E., Pohlenz, J., & Coenen, M. (1997) ‘Atypische myoglobinurie der weidepferde.’, Pferdeheilkunde, 13(1), pages 27-34.

- Dunkel, B., Ryan, A., Haggett, E. and Knowles, E.J. (2020) ‘Atypical myopathy in the South‐East of England: Clinicopathological data and outcome in hospitalised horses.’, Equine Veterinary Education, 32(2), pages 90-95.

- Fabius, L. S., & Westermann, C. M. (2018) ‘Evidence-based therapy for atypical myopathy in horses.’, Equine Veterinary Education, 30(11), pages 616-622.

- Fagan, M. M., Pazdro, R., Call, J. A., Abrams, A., Harris, P., Krotky, A. D., & Duberstein, K. J. (2017) ‘Assessment of oxidative stress and muscle damage in exercising horses in response to level and form of vitamin E.’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 52, pages 80-81.

- Finno, C. J., Valberg, S. J., Wünschmann, A., & Murphy, M. J. (2006) ‘Seasonal pasture myopathy in horses in the midwestern United States: 14 Cases (1998-2005).’, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 229(7), pages 1134-1141.

- González-Medina, S., Ireland, J. L., Piercy, R. J., Newton, J. R., & Votion, D. M. (2017). ‘Equine atypical myopathy in the UK: Epidemiological characteristics of cases reported from 2011 to 2015 and factors associated with survival.’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 49(6), pages 746-752.

- González‐Medina, S., Montesso, F., Chang, Y.M., Hyde, C. and Piercy, R.J. (2019). ‘Atypical myopathy‐associated hypoglycin A toxin remains in sycamore seedlings despite mowing, herbicidal spraying or storage in hay and silage.’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 51(5), pages 701-704.

- Katul, G.G.; Porporato, A.; Nathan, R.; Siqueira, M.; Soons, M.B.; Poggi, D.; Horn, H.S.; Levin, S.A. (2005) ‘Mechanistic analytical models for long-distance seed dispersal by wind.’, American Naturalist., 166, pages 368–381.

- Kranenburg, L. C., Westermann, C. M., de Sain-van der Velden, M. G. M., de Graaf-Roelfsema, E., Buyse, J., Janssens, G. P. J., van den Broek, J., & van der Kolk, J. H. (2014). ‘The effect of long-term oral L-carnitine administration on insulin sensitivity, glucose disposal, plasma concentrations of leptin and acylcarnitines, and urinary acylcarnitine excretion in warmblood horses.’, Veterinary Quarterly, 34(2), pages 85-91.

- Unger, L., Nicholson, A., Jewitt, E. M., Gerber, V., Hegeman, A., Sweetman, L., & Valberg, S. (2014). ‘Hypoglycin A Concentrations in Seeds of Acer Pseudoplatanus Trees Growing on Atypical Myopathy-Affected and Control Pastures.’, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 28(4), pages 1289-1293.

- van Galen, G., Marcillaud Pitel, C., Saegerman, C., Patarin, F., Amory, H., Baily, J. D., Cassart, D., Gerber, V., Hahn, C., Harris, P., Keen, J. A., Kirschvink, N., Lefere, L., Mcgorum, B., Muller, J. M. V., Picavet, M. T. J. E., Piercy, R. J., Roscher, K., Serteyn, D., Votion, D. M. (2012). European outbreaks of atypical myopathy in grazing equids (2006-2009): Spatiotemporal distribution, history and clinical features. Equine Veterinary Journal, 44(5): 614-620.

- Verheyen, T., Decloedt, A., de Clercq, D., & van Loon, G. (2012). ‘Cardiac Changes in Horses with Atypical Myopathy.’, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 26(4), pages 1019-1026.

- Votion, D. M., & Serteyn, D. (2008). ‘Equine atypical myopathy: A review.’, Veterinary Journal, 178(2), pages 185–190.

- Votion, D.M., François, A.C., Kruse, C., Renaud, B., Farinelle, A., Bouquieaux, M.C., Marcillaud-Pitel, C. and Gustin, P. (2020) ‘Answers to the frequently asked questions regarding horse feeding and management practices to reduce the risk of atypical myopathy.’, Animals, 10(2), page 365.

- Votion, D.M.; Habyarimana, J.A.; Scippo, M.L.; Richard, E.A.; Marcillaud-Pitel, C.; Erpicum, M.; Gustin, P. (2019) ‘Potential new sources of hypoglycin A poisoning for equids kept at pasture in spring: A field pilot study.’, Veterinary Record, 184, page 740

- Votion, D.M.; Linden, A.; Delguste, C.; Amory, H.; Thiry, E.; Engels, P.; Van Galen, G.; Navet, R.; Sluse, F.; Serteyn, D. (2009) ‘Atypical myopathy in grazing horses: A first exploratory data analysis.’, Veterinary Journal, 180, pages 77–87.

- Westermann, C. M., van Leeuwen, R., van Raamsdonk, L. W. D., & Mol, H. G. J. (2016). ‘Hypoglycin A Concentrations in Maple Tree Species in the Netherlands and the Occurrence of Atypical Myopathy in Horses.’, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 30(3), pages 880-884.

- Żuraw, A., Dietert, K., Kühnel, S., Sander, J., & Klopfleisch, R. (2016). ‘Equine atypical myopathy caused by hypoglycin A intoxication associated with ingestion of sycamore maple tree seeds.’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 48(4), pages 418-421.